People can also download version 1.0 Guide as PDF here

The TODO Community is grateful to receive corrections and suggestions for improvements via this repo, which contains TODO guide’s updated documentation with the most recent version

- Introduction

- How to contribute to OSS projects

- Starting open source projects

Introduction

Goal and target audience

This guide is about how to contribute to or to launch an open source project (also called “outbound open source”) as a company. It aims to describe a complete and lean process, that can be implemented in companies of any size (large but also small or medium sized organizations). Companies can tailor the proposed procedure to their needs. I.e., depending on the size and situation of the company not all steps need to be implemented.

Maturity levels

Corporate adoption of open source software (OSS) can typically be classified with a model of maturity levels. These levels describe how OSS is used in an increasingly effective fashion to drive value and address business needs. One of the distinguishing factors for the different maturity levels is how outbound open source is handled in an organization. The insight that influencing the open source ecosystem is mainly done by participation in and contributing to open source projects is seen as a critical factor.

A typical maturity model of corporate open source adoption looks like this (see for example Haddad: Open Source Program Offices):

- Denial - No or unconscious use of open source

- Consumption - Passive use of open source software

- Participation - Engagement with open source communities

- Contribution - Pragmatic contributions to open source projects

- Leadership - Strategic involvement with open source to drive business value

To advance from one level to another, certain initiatives and structural and organizational elements are required.

Going from consumption to participation, for example, will start with informal engagement and low-effort activities such as reporting bugs in upstream projects, which typically is driven by technical needs. On that level, decisions about open source contributions will normally be ad-hoc and be taken for individual cases only.

Establishing dedicated decision making processes and formalizing contribution policies will lead to the next level. A typical step on this level is to establish an Open Source Program Office to support open source engagement and maintain an open source strategy and processes.

On the leadership level, contribution processes are mature and scale. Corresponding tool chains are implemented. Own projects with the goal to create new open source communities are started if that’s required and appropriate. This will typically come with leveraging open source foundations to enable cross-company collaboration to strategically use open source to accelerate creating business value.

A company may decide to not progress to levels which are based on more contributions, and it’s of course possible to build mature processes to consume open source software without contributing. In most cases, there will be some pressure to contribute back, though. This can arise from practical technical needs (missing functionalities or required bug fixes are typical reasons for contributing to open source projects), from the expectation to take responsibility in the open source ecosystem, or from the desire to reap the full benefits of the open source model.

How companies manage open source: Open Source Program Offices

An increasing number of organizations realized the tasks of managing open source in an enterprise and complex relationships that are inherent to the open source ecosystem when they are advancing in their engagement in open source. For this reason, many of them started Open Source Program Offices (OSPOs), something called differently, for example Open Source Technology Centers, Open Source Community Development Team etc. OSPOs are a designated place where open source is supported, nurtured, shared, explained, and grown inside an organization. With such an office in place, businesses can establish and execute on their open source strategies in clear terms and responsibilities, giving their leaders, developers, marketers, and other staff the processes and tools they need to make open source a success within their operations.

The TODO Group offers a set of guides on how to get started with an OSPO. Companies that are new to this topic, might want to first take a look at How to create an open source program

Motivation for open source contribution

There is a broad spectrum of motivations for contributing to open source projects or starting new projects. Here, we can only list some examples.

Build software faster and better

Consuming open source software typically increases the development speed and decreases development costs since one builds upon existing code and a working and tested functionality. One risk however is that required features or bug fixes are not provided by the community as quickly as needed. To mitigate that risk, it might make sense to build up the required skills and create these bug fixes and/or features yourself. Contributing them back to the upstream projects has important benefits:

- Integrating “own” features into upstream projects makes maintenance a lot easier

- Upstream versions can be directly used in own products and services

- More features are obtained in shorter period of time

- Higher quality is achieved in shorter period of time

- Support available from core experts

Exercise strategic influence

In addition to the benefits of open source software wrt. development velocity and quality mentioned above, contributing to open source projects can also be important from a strategic point of view. In the open source world, reputation and the ability to influence is typically build up by engaging in the community and by contributing. Thus, contributions to open source projects can help to …

- influence the direction of upstream open source projects

- gain (co)copyright on open source software packages

- access to the creativity of everyone interested in software

Companies sometimes have the tendency to use money to exert influence. With open source projects this is not the most effective method. The currency of influence is contributions, because open source projects are usually much more driven by the work of individuals than the decisions of committees. So contributions work much more directly and effectively than being a member in an organization or paying for support or other services.

Open source communities (particularly those run by the big open source foundations) provide a neutral place for collaboration between companies and other organizations. Thus, an open source approach could offer new ways of collaboration with suppliers, customers, partner and even competitors, just to mention industry- or domain-specific projects such as Linux Foundation Energy or Eclipse Tractus-X. Establishing open source communities can also be a powerful means to create and maintain ecosystems and to establish de facto standards.

Attract, grow and retain talents

Software (and therefore also open source software) becomes more and more ubiquitous in many products and areas. Thus, for many companies it is crucial to have a skilled and motivated software development workforce. This is not only true for software or cloud companies, but also for companies from other segments, such as traditional hardware producers who integrate software into their products more and more, or any other company which is becoming more dependent on software due to accelerating digital transformation. An open source strategy including open source contributions and community engagements supports this:

- increase developer satisfaction

- improve quality and boosts developer skills by peer review of each contribution by core experts

- make company visible as an attractive employer

- improve company’s reputation, and with it the standing of developers in their communities

Give back and keep open source sustainable

Open source software development is living from its communities. As mentioned above, the consumption of open source software helps to decrease costs and speed up development, but that’s only possible because there is the community behind these projects maintaining the software. To keep the open source development model sustainable, each consumer of open source software has therefore the responsibility to think about ways how to support these projects. These are some ways of engagement and support:

- contributions in terms of code, documentation, time (by testing software, for example)

- monetary support (some important projects are maintained by developers who do this in their spare time and thus can only invest limited time in the project)

- executing and supporting hackathons

It is important to understand that though open source software has no license costs when consuming it, it is not available for free. To keep these projects attractive for its consumers, steady engagement and support is required. That’s why it is important to have a strategy for open source contributions in place.

How to contribute to OSS projects

Building better relationships with the open source ecosystem has its own set of challenges, but it becomes easier if you have a clear plan to follow. Here are some guidelines to a number of practices that organizations can adopt.

Define your open source goal and strategy

Your open source strategy connects the plans for managing, participating in, and creating open source software with the business objectives that the plans serve. This can open up many opportunities and catalyze innovation. The TODO Group offers a dedicated guide to Setting an Open Source Strategy

Establish open source guiding principles and processes

Guiding principles

The procedure described in the following is designed to ensure that the company interests and its employees are protected. We also need to make sure that contributions are in line with copyright law, export regulations, data protection regulations and open source development best practices. On the other hand, the procedural burden for all to be involved stakeholders shall be low and the approval procedure should not take too much time.

Responsibility: decision rests with unit

- The approval procedure is the responsibility of the organization that financed the development of the code in question

- If the affected code/IP is used, co-developed or co-financed by other units, involve them as stakeholders in the release decision

General structure and scope of the process

Lean procedure

- The tasks to be carried out by the developer should be clear, simple, and cause as little effort as possible

- The potential complexity of the “backend tasks” should not be visible to the developer. The current status of the request shall be visible to the developer

Boundary conditions

- Protect our employees and our business interests

- Act in compliance with law as well as with internal and external regulations

- Provide transparency to the decision makers on what and how much of the companies’ code and IP will be affected by the publication

- All the contributions shall be made with the “company”-email (similar for the GitHub activity) so that all contributions of the company can be identified easily

- Respect the rules and customs of the OSS ecosystem and of the target OSS project

Process for expressing company approval for contributions

Why is it needed?

Why is there a need for a certain procedure at all?

First of all, the copyright law requires it.

For example, the German copyright act states in Section 69b: Authors in employment or service relationships (1) Where a computer program is created by an employee in the execution of his duties or following the instructions of his employer, the employer exclusively shall be entitled to exercise all economic rights in the computer program, unless otherwise agreed.

Source: German Copyright Act

This means that all the software developed in this context is the property of the employer - i.e., the company the developer is working for. At least the German copyright act does not limit the proprietorship to code developed during working hours or within the company IT infrastructure, it only scopes the context.

Secondly, a procedure is required to protect the company’s business interests as well as to protect the employee. Finally public code is like the business card of a company as well as of the developer who has written the code.

Outbound CLA

Some OSS projects as well as some OSS Foundations require a Contributor License Agreement (CLA) before they accept contributions. We know at least two different types of CLAs:

- Corporate Contributor License Agreement (CCLA)

- Individual Contributor License Agreement (ICLA)

Whether none, one or both are required for contributions is usually described in files like CONTRIBUTING.md in the project repositories. The CCLA and the ICLA authored by the Apache Foundation are the de facto standard of CLAs and many OSS projects have adopted either one or both.

The purpose of a CLA is to provide confidence to the OSS project that the contributor is entitled to submit the contribution. A Developer Certificate of Origin (DCO) is a an alternative approach and more lightweight compared to a CLA.

Some CLAs also require to transfer additional rights to the project such as the right to release the code under an additional, often proprietary license. This is an asymmetric setup which puts contributors at a disadvantage. Therefore most companies will not contribute to these kind of projects.

The price of improved confidence for the OSS project is more overhead in the organization the contributor is working for. Especially in case of large corporations with several affiliates the effort of evaluating, signing and maintaining a CCLA shall not be underestimated.

Why is a CCLA causing additional effort in large organizations? Let’s briefly look at the CCLA of the Apache Foundation as an example:

- The CCLA is a contract - in many organizations the “four eyes principle” is implemented - a contract has to be signed by two persons, who have the right to sign contracts in the name of the organization - the required involvement of probably two more stakeholders requires additional effort in briefing them

- Usually a CCLA covers not only the specific legal entity the contributor is working for, it also covers all affiliates:

- For legal entities, the entity making a Contribution and all other entities that control, are controlled by, or are under common control with that entity are considered to be a single Contributor. For the purposes of this definition, “control” means (i) the power, direct or indirect, to cause the direction or management of such entity, whether by contract or otherwise, or (ii) ownership of fifty percent (50%) or more of the outstanding shares, or (iii) beneficial ownership of such entity

- The CCLA includes besides the copyright grant a patent grant. This is fine, nevertheless inside the organization the “IP department” needs to be involved in the evaluation process of the CCLA and for the specific contribution the “IP department” need to sync with all affiliates

- The CCLA needs to be analyzed by the “Legal department” of the organization.

Some CCLAs require that the copyright of the contributions are assigned to the OSS project/Foundation. Copyright assignment is a topic which causes even more effort and might not be accepted at all.

Besides the above-mentioned additional effort the CCLA adds additional “maintenance effort” to the organization, because it requires that the organization nominates all entitled contributors by name to the CCLA requiring party.

It is your responsibility to notify the Foundation when any change is required to the list of designated employees authorized to submit Contributions on behalf of the Corporation, or to the Corporation’s Point of Contact with the Foundation.

The signed CCLA has to be made available inside the organization - This can be done via publishing the CCLA on the OSPOs website at a location which can be found easily be the employees (e.g., it might be useful to have a “top level page” named CCLAs, this page then contains a list of “signed CCLAs”, a list of “CCLAs under evaluation”, and a list of “denied CCLAs”.)

All affiliates need to be informed and a procedure needs to be defined how the affiliates can nominate/de-nominate contributors working for them. This becomes even more challenging in case an affiliate has no access to the intranet of the signing entity. In this case the signed CCLA or the information about the signed CCLA needs to be sent to the OSPOs of all affiliates, in case an affiliate has no OSPO set up, the information must be routed to the function, which is in charge of software development. All affiliates need to provide the names of nominated contributors or former contributors, who shall not be entitled anymore to do contributions to the OSPO of the signing entity, which then must inform the Foundation/project about the change of the list of contributors.

Publishing the list of contributors inside the organization and disclosing it to the Foundation/project might also require the approval of the data protection officers of the involved entities

This additional effort may hold organizations off to contribute small bug fixes or patches or even new features to the upstream OSS projects and puts them to risk of private forks and thus a lot of additional development effort in the long run. Thus the decision not to contribute needs to be taken very carefully.

A DCO in contrast to a CLA is a much more lightweight procedure. It was introduced to enhance the confidence that contributions to the Linux kernel are made “legally correct” by the contributors. The DCO version 1.1 is used by many OSS projects.

The main difference of a DCO compared to a CLA is, that a DCO is not a contract, it is a kind of attestation of the specific contributor that they are entitled to submit a concrete contribution. All the effort which has to be spent to get a CLA signed and maintained is not needed. The only tasks which have to be carried out are:

- Evaluation of the DCO by the “Legal department”

- Evaluation by the “IP department”

- Evaluation by the specific contributor, whether it is acceptable for them

Since the DCO version 1.1 is the “standard” the “Legal”- and “IP department” only have very little effort to spend.

Procedure for contributions to existing projects

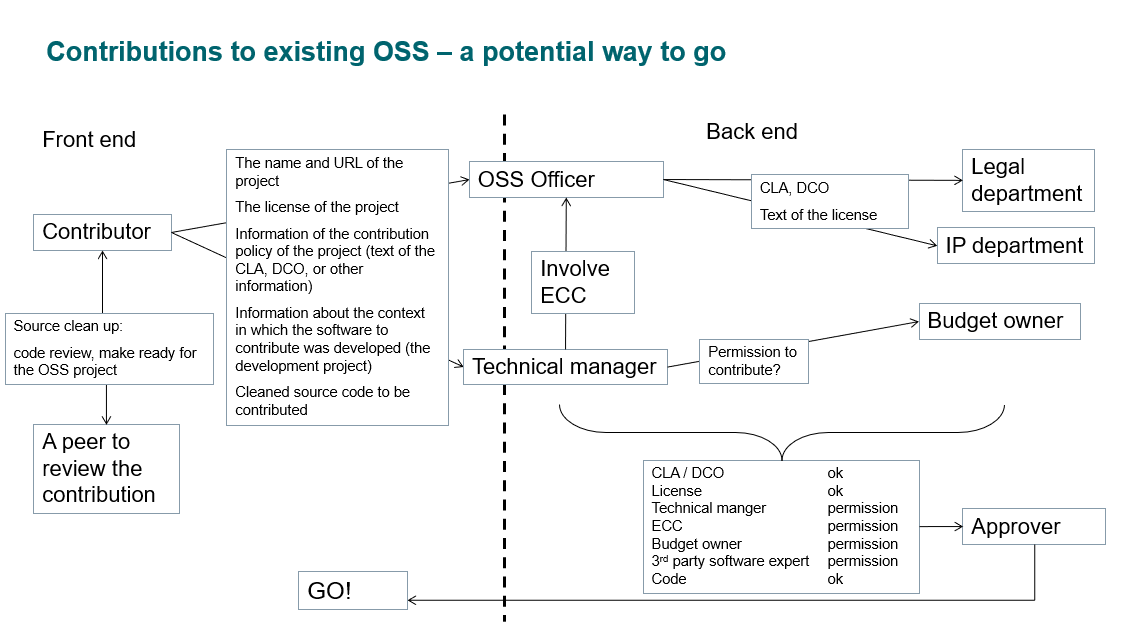

The more complex the business environment in which the code to publish was developed, the more stakeholders need to be involved. The picture below shows a procedure that involves all functions, even in a complex setup.

Abbreviations used:

- CLA = Contributor License Agreement

- DCO = Developers Certificate of Origin

- ECC = Export Control and Customs

- IP = Intellectual Property

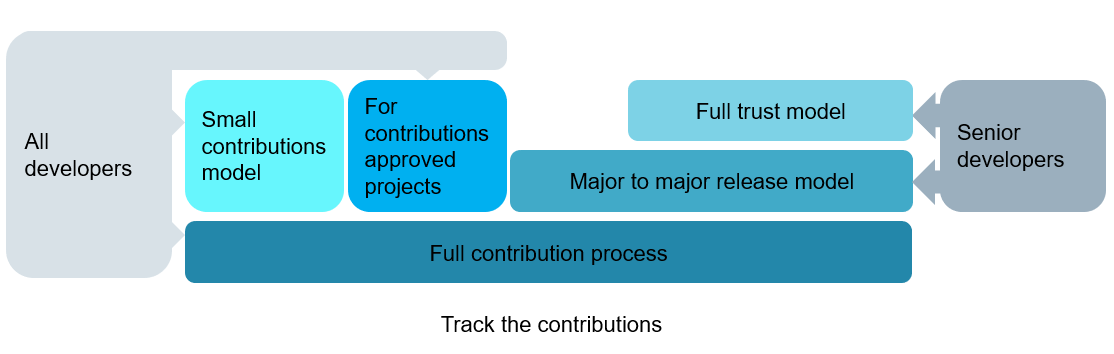

The procedure shown above is not suited for frequent contributors and/or contributors who are working “upstream” in their daily work. For these developers different procedures need to be established in order to avoid loading them with “unproductive” work. Different contribution models can be established in an organization to serve different needs.

Contribution models

The following approaches are suited for such developers:

- Small contributions model

- Major to major release model

- Full trust model

Small contributions model or trivial contributions

A small or trivial contribution is a rather small and simple change to already existing open source software. Typical cases found in this category are bug fixes with no or low Intellectual Property value.

A change is not trivial if:

- Functionality is added or changed.

- The interface of the open source software component is changed.

- It is an optimization that more than insignificantly increases performance.

- It contains a design or an algorithm that wouldn’t be obvious for a software engineer.

This procedure scopes small contributions. It can be implemented for small or trivial contributions following the initial contribution to a particular OSS project or component. The initial contribution has to undergo the entire procedure described above, because CLAs/DCOs etc. have to be checked and signed in case the particular project requires them. After the initial contribution all subsequent small contributions can be contributed directly to the OSS project without the need to follow the defined process no matter which version of the OSS project.

Major to major release model

This procedure scopes the release cycle of the OSS project to which contributions shall be made. It has the same “starting point” like any other contribution - the initial contribution must implement the entire procedure in order to check CLAs/DCOs and to have the documented permission to contribute to a specific project. After the initial contribution all subsequent contributions during the development of a new major release can be contributed to the OSS project without the need to go through the approval process. There is no size limitation for contributions. The contributions can range from a trivial bug fix to adding new features, changing interfaces, refactoring and so on. After the release of a major version of the project a new approval procedure has to be kicked off for the first contribution after the major release.

Full trust model

The full trust model can be applied to developers who have already successfully worked under the major to major release model. It is an incentive for the employee and a sign of trust of the employer towards the employee. Basically it is the permission for the developer to work “upstream” without any approval procedure. Since this model shall only be applied after the developer worked successfully under the major to major release model, there is no need for an “initial” contribution with the entire approval procedure, although it makes sense in order to have it documented.

The major to major release model as well as the full trust model shall only be executed by senior developers, who are specially trained in copyright principles, have a good understanding of the business interests of the company they are working for, practice “an ownership culture” and have already deep experience in the open source ecosystem.

In order to track all the contributions the developers shall contribute with their official email address.

Approving projects for contributions

Another model is to provide approval for specific projects. These projects are checked, e.g. by the OSPO, and if everything is in place to allow contributions, they are cleared for contributions by employees. Then there is no individual approval for each specific contribution required. But if the general conditions of the project change, such as license or introduction of a CLA, etc. the project needs to be cleared again by the OSPO

Prerequisite for such a model is that contributors are qualified to do contributions autonomously. This can be achieved by making sure contributors have received training and/or tracking and approving who can contribute to which repository.

Spare-time contributions - also known as “moonlighting”

What to do in case an employee wants to contribute to OSS projects in their spare time which do not fall under the corporate context?

In this case the copyright ownership stays with the developer (assuming they are not developing for another entity). In order to provide clarity the following procedure can be implemented:

The developer informs his or her manager about the intention to contribute to a certain project (which is out of scope of section 69b German Copyright Act). In case the manager has no objections he/she draft a small note with, at least, the following content:

- Date of the meeting

- Project(s) the employee wants to contribute to

- Estimated hours per week

- Approval by the manager

- Signature of the developer

- Signature of the manager

The note can be sent to the HR department to keep it in the personnel record of the employee.

This procedure provides transparency especially in the context of large enterprises, acting in many different software technology areas.

The example below shall illustrate why such a procedure makes sense:

A developer may, for example, implement Linux kernel drivers according to his duties. Another area of interest of the developer is for example AI and the developer wants to contribute to an AI project during his spare time. Given that the AI project has nothing to do with Linux kernel driver development, the developer holds copyright on his contributions and the copyright ownership is not transferred to the employer. The developer can contribute code without the need of an approval by his employer.

But what about when the developer decides to move to another department inside the company, which develops AI. All of a sudden the former “moonlighting” is now covered by section 69b of the copyright act and the copyright owner now is the employer.

The above described procedure provides transparency about the copyright ownership and its change during the time.

Trainings

Contributors to open source projects will need to act with a certain degree of autonomy to be effective. For some corporate software developers it will also be new to participate in open source communities. For these reasons it is important to support corporate contributors and provide them with training or similar means to develop the understanding and skills to act as good citizens of the open source world on behalf of your company.

This can be achieved with mentoring, good practice guides, or trainings which cover the following topics:

- Essentials of legal implications of open source, such as copyright, licensing, CLAs, DCOs, trademarks

- Awareness of your corporate rules and policies for contributing to open source

- Open source community culture

- Typical open source development procedures

- Open source governance in its different forms such as foundations or single-vendor projects

- Working in public

- Dealing with conflict of interests between open source project and company

- Where to get internal support in case of doubt or questions

Starting open source projects

Motivation

There are many good reasons to start own open source projects. See the introduction for some of the motivations for doing this.

Launching a new OSS project is comparable to a product introduction and it is, at first hand, a software development project - there is no difference to an internal software development project concerning planning, budget, staffing, testing etc. - the only difference is that everything happens in the public area. Be aware that publicly available source code is the “business card” of the organization to the software ecosystem, and it is also the “business card” of its maintainers.

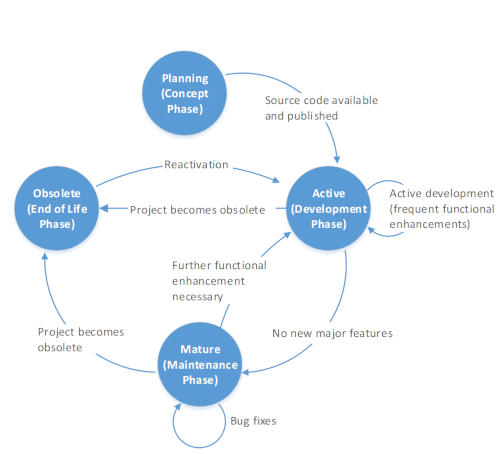

When thinking about to start an own OSS project there are several phases you should consider:

Project life cycle

The life cycle of an open source project describes the stages in which the project evolves, from its conception to its retirement or end of life stage. Typically, a project originates to solve a specific problem. It may become obsolete either because the problem does not exist anymore or because other projects are better suited to solve the problem. The figure below shows the different stages an open source project may undergo.

Planning or Concept Phase

This is the starting point of every open source project. It can also be referred to as the “initiation phase”. Normally, at this stage, only an idea exists or a specific problem has been identified which requires solution. In this phase, the open source project typically has the following characteristics:

- The problem that the project intends to solve has been clearly defined

- There is either no source code available yet or the source code is only internally available. In the first case, the project only exists as idea; in the second case, the project may have been started as an company-internal project and has not been published yet

- Possibly, the idea has been already shared with the community to get feedback. However, note that sharing such ideas that have only been discussed company-internally requires approval in advance.

Before starting a project, it is reasonable to get answers to the key questions:

- Is it possible to join efforts with an existing open source project?

- Can we launch and maintain the project using the OSS model?

- What constitutes success? How do we measure it?

- Can we financially sponsor the project? Do we have an internal executive champion?

- Will the project be able to attract outside enterprise participation (from the start)?

- Is there enough external interest to form and grow a developer community?

(Source: Linux Foundation)

In addition, the following aspects should be considered in the planning phase:

What is the goal of the project and will it solve the problem?

Are there enough resources not only to start, but to support the project in the long-term? (You also need to obtain and ensure sponsorship)

An appropriate license must be selected. The license should support the project goal.

The legal requirements for contributions must be decided (if, for example, contributors must sign a CLA or DCO). Maybe your company has a standard approach for that.

Execute additional checks. For example:

- Make sure that all license obligations are fulfilled

- Export control: Under certain circumstances it might be required that the project must have an export control classification number (ECCN), for example.

- Check that the publication is not in conflict with existing trademarks.

The checklist of the Linux Foundation contains a comprehensive set of topics you might want to consider

Does it make sense to donate the code to a vendor-neutral, non-profit organization (that is, an open source foundation), or retain some control by owning and running the project under the responsibility of your company? Note that this decision depends on the project and may also be taken later in the life cycle. Typically, a project first needs to be published and generate interest in the community before it is handed over to a third-party organization.

Set up an open source project governance. It establishes how to contribute to or maintain a project.

Determine the tools and infrastructure the project members will use

Carry out a technical review

Ensure that all critical content is removed from the project before publishing it. For example:

- Dependencies to non-public components

- Internal comments, references to other internal code, and the like

- Access tokens and the like

Ensure that the coding style is consistent

Where will the code be published? Typically, it will be in a company-owned organization on a code hosting platform such as GitHub.com or GitLab.com but, depending on the technology, other potential publishing channels exist (for example, NPM, Maven central, PyPI)

Does it make sense to publish binaries? If yes, where?

Define your web site and communication: What can you do to make your project known? Does it make sense to create a web site for the project? Are there working groups?

Plan your project life cycle

Active or Development Phase

Once the project has got an approval for open sourcing and the code is available and published, the project has entered the active development phase. In this phase, the open source project typically has the following characteristics:

- The source code is publicly visible

- The project community is actively managed

- The project can receive contributions from the community

- Further development is ongoing, based on incoming requirements

- A dedicated team is working on the project and provides support

- Potentially, to make the project better known and to attract more users and contributors, the project is being promoted in talks at open source events, conferences, and so on.

During the active phase, the following aspects should be considered:

- Do marketing: Make the project better known (for example through blog posts, reaching out to potentially interesting parties/companies, talks at conferences)

- Invest in building and managing the community

- Care for full transparency, every decision shall be made in the public, even if there is no external community yet. This is very important because interested organizations are able to follow all decisions and to build up trust in the project

- Carry out a health check of the project and its community (that is, perform a review of the defined KPI’s and goals)

- Check 3rd party contributions

- Plan further developments

- Support by fixing bugs and security issues

Mature or Maintenance Phase

At a certain point in time, an open source project becomes mature. This can also be referred to as the “maintenance phase”, meaning that only error corrections are made and normally no new functionality is developed. The following aspects characterize this phase:

- The project is being used actively, but from a functional perspective it can be considered as complete or at least no major functional enhancements are necessary

- Contributions mainly focus on bug fixes. Functional enhancements are only minor and are done rarely

- A dedicated team still provides support for the project, but with relatively low efforts

- The team still has to take care of the community, but normally less effort is required compared to projects that are in active development.

- It is good practice to clearly communicate that the project is in the maintenance phase and no or only limited further development can be expected

- The team should perform regular health checks of the open source project and the external community

- Bug fixes and security fixes are still required

Obsolete or End of Life Phase

An open source project in this phase is characterized by the following properties:

- There is no or only very minor interest in the project

- No further contributions take place

- There are no further developments and no incoming requirements

- No further support takes place

- Possibly, there is no project team available anymore

During this phase, it is important to consider the legal implications and come up with the appropriate documentation and communication with the community. Since the project has been published, it might be in use. Therefore, the community needs to be informed that the project is no longer maintained. Furthermore, once in this phase the decision must be made whether to archive the project or remove it completely.

Legal and governance considerations

Which license to select

Choosing the license for a new open source project is an important decision. Without a license the code can’t be used by anybody, even if the code is publicly available, for example in a GitHub repository. Choosing a license which is not approved by the OSI as an open source license also effectively makes the code proprietary. This will make it harder to get adoption, especially in most corporate setups, where processes are usually built around the well-known standard open source licenses.

Open source licenses vary in the rights and the obligations they give to users. All open source licenses approved by OSI give users the right to use the software without restriction to specific users or use cases. When distributing open source software, and especially when distributing it with modifications, the obligation vary. The spectrum goes from the so-called copyleft licenses such as the GPL, which require to pass on rights given by the license to users, to permissive licenses, such as the Apache or the MIT license, which allow incorporation in proprietary systems.

When choosing a license the following questions have to be considered:

- What’s the goal of the open source project? When broad adoption is a priority, a permissive license might be a good choice, when the focus is on building a contributor community, more reciprocal licenses might have advantages.

- Is there a license suggested or required by the ecosystem where the project is positioned? If it is meant to become part of a foundation or an umbrella project then there might be a strong preference for a license, e.g. the Apache license for Apache projects, or the GPL for Linux kernel drivers.

- How does the license interact with your business model? When the software you are going to open source is supporting other parts of your business, a permissive license might accelerate adoption. If you are also selling proprietary version of your software, a copyleft license might be a stronger differentiator.

- Are there dependencies or other incorporated code which limit the choice of licenses? For example when incorporating GPL code, the resulting project has to be GPL as well.

Answering these questions can be challenging and opinions will vary. A simple starting point can be the choosealicense.com. There is a lot of comprehensive material available from various sources, e.g. Open source licenses: What, which, and why.

It is advisable to set up policies for license selection, so that the decision process is simplified when starting new projects.

Contributor License Agreement (CLA), Developer Certificate of Origin (DCO)

When running an open source project you need to decide how you are going to check code provenance and if you need additional rights from contributors which are not given by the license. There are mainly three ways how to handle that:

“Inbound=Outbound” - Contributions are accepted under the same license as the project distributes its code. There is no additional paperwork. This is a symmetric setup, where contributors, maintainers, and users have the same rights under the chosen license. It has the lowest barrier for contributors. Some things such as changing the license of the projects become difficult, because that needs approval by every contributor.

Developer Certificate of Origin (DCO) - The DCO was introduced in Linux kernel development and has been adopted by many other projects. It is a statement developers give with each commit by including a “Signed-off-by” statement in the commit message. With this statement developers explicitly declare that they have the rights they need to do the contribution and that they agree that the project is using it. This is still a low barrier, but it gives projects more confidence that code was rightfully contributed. It does not help in cases where the license of the code needs to be changed.

Contributor License Agreement (CLA) - A CLA is an additional agreement between the contributor and the project which gives the project additional rights on top of the rights given by the license. If people contribute on behalf of a company, where the company holds the rights on the work of the contributor, the company has to sign the CLA. There is a variety of different CLAs in use, some mostly confirm the rights already given by the license, some give additional rights such as being able to release the code under a different license, for example when the code is also released under a proprietary license as part of a commercial offering. With a CLA, rights are collected at a central place, so changing the license, or rereleasing the code as part of a product with a different license, is possible. The asymmetry of the agreement, which gives the project more rights than its contributors, can impose a bigger barrier for contributions. Requiring a corporate CLA can also be an insurmountable barrier, especially for large corporations, because the effort and legal implications of checking and signing a CLA might outweigh the benefits of contributing.

You should have a policy for which of these ways you use when. “Inbound=Outbound” is a pragmatic way which can work for most projects. The DCO is a good way to make the contribution process more explicit, especially for larger projects with diverse contributors. The CLA makes contributions more difficult and requires additional administrational work and tooling. To get an impression about the additional effort and difficulties especially large corporations face you can check the section about contributions to existing projects.

Project governance

An important factor for the success of an open source project is its governance. That comprises the rules, policies, conventions, and culture of the collaboration. It determines factors such as how decisions are taken, who is in control, or who can join a project.

In existing projects governance often has emerged over time, has gone from informal procedures driven by the practices of the project founders to more formally defined governance documented in contribution guides or ultimately instituted through a foundation as formal organization hosting the project.

When starting a new open source project you have to decide about how its governance will look like. This goes beyond deciding on a license. You will also have to decide about ownership of assets such as trademarks or domains and the rules how they can be used. And you will have to decide about policies of how people can become committers or maintainers, how releases and roadmaps are made, or how transparent the decision making process is.

For a project which is meant to attract a broad set of contributors it is important to set up governance which provides a neutral ground, is open to participation by diverse participants, and is transparent about its decision making. This can be called open governance. One way to achieve this is to join one of the existing open source foundations. Prominent examples for this are Kubernetes which is hosted by the CNCF or the Eclipse IDE which is part of the Eclipse Foundation.

In other cases a company might want to retain more control about the project. This will limit contributions from others but give more freedom in how to steer a project. It requires that there are enough resources allocated to maintain the project. It still is helpful to implement elements of open governance, such as transparency about planning or a permissive trademark policy to increase adoption of the project. Examples for this would be TensorFlow which is run by Google or Visual Studio Code which is run by Microsoft.

For smaller projects, for example technical tools which emerge from work on other projects, a simple and less formal approach to governance can also work. Here the goal is not primarily broad adoption or building a large community, but transparency and ad-hoc collaboration with interested individuals. Often this kind of project is more driven by technical needs and motivation of developers than by overarching business needs. If such a project is growing its governance can be evolved. This can for example result in a project being transferred to a foundation. Countless examples can be found on GitHub.

More detailed information and possible starting points for open source governance can be found in the Minimum Viable Governance framework or A Legal Issues Primer for Open Source and Free Software Projects.

Different Project Levels

It can make sense to have different levels for new open source projects (“sandbox”, “incubator”, “graduated” - these are the different project levels of CNCF, for example). This is a way to classify your open source projects wrt. adoption, maturity and quality criteria that they have to fulfill. The basic idea is that new projects start in a dedicated space (CNCF calls that “sandbox” - at Meta, that’s the “Incubator”). In this space, projects can evolve and check if they reach the goals that have been defined in terms of adoption and quality. If they do, they can be promoted to the next level. If they don’t, it might be decided to sunset them.

Community management

For the majority of open source projects, starting a community around that project and receiving contributions is an important if not the primary goal (however, there are also projects where the primary goal for open sourcing is not the creation of a vivid community - for example building trust by making the source code visible, in this case receiving contributions might have a lower priority). Such a community does not take off by itself. Starting it and keeping it alive requires planning as well as budget and resources. Initial and ongoing activities comprise:

Promote the project

This includes presenting at conferences, hosting or sponsor key events, and building new initiatives and programs in your community

Create a welcoming environment

This includes creating open-source project policies, guidelines (basic instructions for maintainers, installation process, instructions for end users) or improve main project communication channels (forums, chat discussions, etc)

Facilitate collaboration

Building mentoring programs, adding project documentation (such as how to contribute, how to write and run tests, how the governing board is elected, etc )

It’s advisable to assign a community manager to the project who takes care of these tasks. The TODO Group Guide Starting an open source project contains more information in its chapter “Build the community”. For further reading, we recommend the TODO Group Guides Building an inclusive open source community and Building leadership in an open source community.

Code of conduct

Creating a welcoming environment where people are safe from harmful behavior by others is an important part of maintaining a healthy community. It is especially important to support a diverse community, where there is no discrimination of under-represented groups, and explicit or implicit bias gets addressed.

A common element in maintaining a healthy community environment is a code of conduct which makes rules for accepted and unaccepted behavior explicit and defines how unacceptable behavior is dealt with. There are examples and templates which can be used as a base for your code of conduct. One popular reusable code of conduct is the Contributor Covenant which is used by projects such as Kubernetes, git, Node.js, and many more.

As a company you need to provide a contact email which can be used to report code of conduct violations. You need to make sure that this address is monitored by people who can react in a timely manner and have the competence and ability to initiate adequate actions to address these issues.

Technical considerations, tooling and best practices

Appropriate tooling can safe a lot of time and help to automate processes significantly. Curated list of awesome tools to manage open source contains a comprehensive list of proven and recommendable tools.

User management

Normally, Git providers (GitHub, GitLab, Bitbucket etc.) offer means to define teams of individual users and to define (access) rights on team and on individual level. To be able to use the service of a Git provider, engineers have to create a corresponding account. This account has nothing to do with the company-internal account of an engineer. This imposes some challenges since the access rights of an engineer for an external repository might depend on their role in the company or whether they are still working for the company (let’s assume that an engineer got comprehensive rights for external repositories when they were working for your company and that they now left the company - you might want to adjust the access rights). But how to do that since the external account of an engineer at a Git provider is independent from his company-internal user account? Somehow a mapping between both accounts is needed. For GitHub there’s the open source tool opensource-portal available that can help to create such a mapping. It can also be used to implement a self service for joining of GitHub organizations. As part of the process, the tool creates the mapping between the GitHub.com account and the corresponding company-internal user account. The mapping is stored in a database. Based on this, it is easy to create some tooling that regularly checks if all users that are contained in that database are still employed by your company and trigger some activity if that’s not the case.

Setting up a repository

It is good practice that a repository contains a certain set of files (the health files). These files contain the basic information about the repository such as description, code of conduct, license, contribution guidelines etc. These files are often provided in markdown format, but could - depending on the Git provider - be provided in different formats such as AsciiDoc. Here, we assume the default format (which is markdown) and thus use the file suffix .md.

README.md

This file is displayed as the homepage of the repository. It typically contains information such as repository description, dependencies as well as download, installation and configuration instructions.

LICENSE or LICENSE.txt

Contains the license text for the repository.

CONTRIBUTING.md

Contains information and instruction about how contributions can be made.

CODE-OF-CONDUCT.md

Contains the code of conduct for the repository.

GOVERNANCE.md

Contains information about project governance.

SECURITY.md

Contains instructions about how to report security vulnerabilities for the repository.

SUPPORT.md

Contains information about how to receive support in case of problems.

The README.md and the license text file should be there for all repositories. The other files can be considered as optional and only be created if they are required (if, for example, no contributions are accepted, this information could be put into the README.md and a CONTRIBUTING.md is not necessary).

To make sure that a certain set of health files is always created, there are different possibilities:

One possibility is to use template repositories. These are repositories that contain the required set of initial health files. A new repository can be created/copied from this template repository and thus it contains already the required set of health files. Some Git providers (GitHub, for example) provide specific means to create the required health files per default.

Another possibility is to create repositories with a tool. Such tools create repositories based on some input data via the API’s of the Git provider (GitHub.com, GitLab.com, Bitbucket.org etc.). Thus, they can help that repositories are compliant to the company guidelines (contain the required health files and team structure, for example). Based on such tools self services for repository creation could be offered that allow development teams creating repositories themselves. Often, companies develop such tools for their specific needs. We (the authors of this document) do not know generic repository creation tools.

Providing license and copyright information

License and copyright information must be declared properly for an open source project. This is important for consumers of the project as well as for contributors. Furthermore source code often gets copied from one project to another, this makes it mandatory that all files carry license and copyright information

- for the parts of the project that you / your company developed

- but also for external components (i.e. code developed by external parties) that are part of your repositories

Note that a statement like For license conditions please check LICENSE.txt is not suited.

The REUSE tool from the Free Software Foundation Europe supports the proper declaration of license and copyright information for your project:

- It provides a machine-readable file format for license and copyright information and thus makes it easy for others (scanning tools, for example) to consume that information

- It provides tooling to:

- add license and copyright information to source code files

- download and store license texts

- to lint your repositories to make sure that license and copyright information is available for all files

CLA/DCO Management

If contributors must accept an CLA or DCO before they can submit their contributions, it is beneficial to automate that process as much as possible. The TODO Group provides a list of tools that support the management and the sign-off of DCOs or CLA documents. As an example, we describe the CLA Assistant in more detail.

The CLA Assistant implements a workflow that asks contributors to accept/sign-off a document when a contributor submit the first pull request to a certain repository on GitHub.com. Despite the name of the tool (“CLA Assistant”), it can be used for any type of document that companies require contributors to accept before a pull request can be submitted, including CLAs and DCOs. The document text must be provided as gist on GitHub.com. Which document/gist to be used can be configured on organization and on repository level. The CLA Assistant uses a default logic: If for a certain repository no specific document is configured, the document that is configured on organization level is used. When a contributor submits a pull request for a repository for the first time, the CLA Assistant displays the document text and the contributor can only submit the request if they accept the document. The next time, the same contributor submits a pull request, they can do so without having to accept the document again. The information that the contributor accepted the document for that repository is stored in the database of the CLA Assistant and can be retrieved later on. The CLA Assistant is available as hosted offering on https://cla-assistant.io/ or can be self-hosted.

Credential scanning

Even if open source policies and guidelines explicitly require that credentials such as password, access tokens or other secrets have to be removed from code before it is published, it happens from time to time that unintentionally such important and sensitive data is pushed to public repositories. To detect such situations as quickly as possible (and thus to be able to revoke the published secret and remove that data from public repositories), it is advisable to regularly execute credential scans for such repositories. Luckily, all well-known code hosting platforms (GitHub.com, GitLab.com etc.) provide such scanning services as part of their offering. We strongly recommend to use that services.

Quality criteria / CII Best Practices Badge Program

The Core Infrastructure Initiative (CII) created the CII Best Practices Badge Program. It is now continued by the Open Source Security Foundation. As part of the program, best practices for open source software is defined and a badge system is implemented. Via a web app, projects can self-certify that they meet the criteria and show a corresponding badge on their website. As of today (May 2022), more than 4724 projects did the assessment.

The CII system consists of three levels (Passing, Silver and Gold). They are building on each other (i.e. the Silver level contains all criteria of the Passing level plus additional ones). The criteria are structured in clusters such as Basics, Change Control, Reporting, Quality, Security and Analytics.

The CII Best Practices Badge community is open for contributions (additional criteria, for example).

Overall, the CII Best Practices Badge Program is a good means to verify own projects against commonly accepted best practices. Via the badge, projects can document that they meet these criteria.

Repository Linting

Repository linters are tools that check in an automated way if repositories adhere to the guidelines that a company has defined for its public open source repositories. The TODO Group provides a list of tools that can be used for this purpose. Typically, repository linters check criteria such as:

- Do the required files exist in the repository (license file README.md, CONTRIBUTING.md, for example)?

- Do these files contain the required sections?

- Does the repository have a license that is compliant to the company guidelines?

- Does the repository contain the required badges (the REUSE badge or the CII badge, for example)?

- Repository team structure (a certain team structure might be required - at least two administrators, for example)

- Configuration of the repository (are vulnerability alerts activated?, for example)

However, which criteria they check is company-specific and thus, they normally provide the possibility to configure rules (as JSON file, for example, as the repolinter of the TODO Group does). To retrieve the necessary data to execute these checks, the APIs of the Git provider (GitHub.com, GitLab.com, Bitbucket.org etc.) is used. The result of the check is typically provided in a UI. Another option is to automatically create issues in the corresponding repository if checks fail. Typical usage scenarios for such a linter include:

- Check for guideline compliance before a repository is published

- Regular checks after publication

Build an open source metrics strategy when releasing to open source projects

Once you have established the goals, procedures, and tools for your company’s outbound open source plan, it is always useful to monitor and track the overall health of open source projects the company engages with as they grow and mature.

Before thinking about which tool should be used to track project health, a good alternative on how to do this is to establish a full metrics strategy following the goal-question-metrics approach. This approach is used in communities focused on community health analytics metrics standards and software, such as CHAOSS, one of the projects under the Linux Foundation umbrella.

Defining community health goals

Sometimes it is better to start small and define two or three main goals first before getting overwhelmed by metrics. If you don’t know where to start, CHAOSS offers a set of metrics based on different focus-areas and goals when measuring project health that can help you get started in measuring the health of the open-source projects that matter to your organization:

- Common Metrics

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Evolution

- Risk

- Value

- App Ecosystem

Creating questions and building metrics around

Metrics should be answering specific questions that are aligned with the previous goals established.

For instance, if one of your company’s goals is to understand the community footprint within a project, one good question can be “What’s the presence and influence of organizations within the open source ecosystem?”. In order to solve this, one useful metric can be the Elephant Factor (the minimum number of organizations whose employees perform 50% of the total contributions).

There are great tools to help you measure different community health analytics metrics, for instance, GrimoireLab, LFX, or Augur.

For further information about tools for tracking project health, check this dedicated section from one of the TODO Guides

References and Abbreviations

Abbreviations

- API = Application Programming Interface

- CII = Core Infrastructure Initiative

- CLA = Contributor License Agreement

- CCLA = Corporate Contributor License Agreement

- CHAOSS = Community Health Analytics Open Source Software

- CNCF = Cloud Native Computing Foundation

- DCO = Developers Certificate of Origin

- ECC = Export Control and Customs

- ECCN = Export Control Classification Number

- GPL = GNU General Public License

- ICLA = Individual Contributor License Agreement

- IDE = Integrated Development Environment

- IP = Intellectual Property

- JSON = Java Script Object Notation

- KPI = Key Performance Indicator

- LFX = Linux Foundation Collaboration Metrics

- MIT = Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- NPM = Node Package Manager

- OSI = Open Source Initiative

- OSPO = Open Source Program Office

- OSS = Open Source Software

- PyPI = Python Package Index

References

- Open Source Archetypes: A Framework for Purposeful Open Source (Mozilla)

- Starting an open source project (LF TODO Group)

- Shutting down an open source project (LF TODO Group)

- Marketing open source projects (LF TODO Group)

- Building leadership in an open source community (LF TODO Group)

- Community Health Analytics Open Source Software (LF CHAOSS)

- How to measure the health of an open source community

- Community health files (GitHub.com)

- CII Best Practices Badge (LF Core Infrastructure Initiative)

- DCO version 1.1

- ICLA

- CCLA

- German Copyright Act

Appendix

Managing work vs personal emails in git

In the world of open source, folks may have an online identity that pre-dates their employment with our current organization. Simultaneously, the organization may want contributions done on their behalf to happen with corporate emails.

One way that folks can solve this is by encoding their commit email on a per-repository basis, like:

git config user.email "simba@special-email.example.com"

If you work with several repositories, this will become difficult to manage and easy to forget. Instead, we can use a feature of git which allows different configurations based on our directory structures.

Our ~/.gitconfig file might look like this:

[user]

name = Simba Lion

email = simba@personal-email.example.org

[includeIf "gitdir:~/my-company/"]

path = ~/my-company/.gitconfig

This sets our default email (which, in this case, is for a personal

account). If we have repositories in the ~/my-company directory, we’ll load an

additional git config file which is located at ~/my-company/.gitconfig. That

file might look like:

[user]

email = simba@very-corporate-email.example.com

Now when our user commits changes, it will use their personal email by default,

or their corporate email for any repositories within the ~/my-company

folder. Note that the name attribute is inherited from the base configuration,

so we don’t need to double specify it.