Setting an Open Source Strategy

The majority of companies that use open source do not necessarily understand the benefits to their organization and do not have a strategy aligned with their business needs. Furthermore, only about half of these companies report practicing basic open source management, such as community development, code maintenance, and the like, according to the latest Future of Open Source survey.

Creating and documenting an open source strategy is an essential first step to realizing ROI with open source as open source can have a positive or negative effect across several dimensions related to an organization: strategic/business, operational, technological and financial. Your open source strategy connects the plans for managing, participating in, and creating open source software with the business objectives that the plans serve. This can open up many opportunities and catalyze innovation.

Why create a business strategy?

Formalizing your organization’s approach to open source management and strategy creates guidelines that boost efficiency and minimize risks. Whether or not you have set a business strategy around your open source efforts, you likely already know that this is important.

The critical first step in increasing your open source investment is to create a strategy document that involves defining what open source means to your organization and creating a shared taxonomy. This will help you maximize the benefits your organization gets from open source, while keeping you out of trouble that can arise from mistakes such as picking the wrong licenses or failing to maintain code properly. Your strategy document can:

- Get leaders excited and involved

- Obtain buy-in at various levels within the company, especially at executive level

- Facilitate decision-making in diffuse, multi-departmental organizations

- Help individuals and inventors make better decisions

- Help build a healthy community around inventions

- Explain your company’s approach to open source and business models and support of its use

- Clarify where your company invests in community-driven, external R&D and where your company will focus on its value added differentiation

“If you do not start with that high-level consensus, driving agreement on the details of the policy and on investments in the process tends to be very hard, if not impossible.”* *- *Ibrahim Haddad, Vice President of R&D and the Head of the Open Source Lab at Samsung, in his book Open Source Compliance in the Enterprise.

Your open source strategy document

Let’s start with the end goal first, and then explain how to get there. Your goal is to detail your open source strategy in a document that everyone from engineering and legal, to marketing and the C-suite can reference. This strategy document will help your team understand the business objectives behind your open source program, ensure better decision-making, and minimize risks.

“At Salesforce, we have internal documents that we circulate to our engineering team, providing strategic guidance and encouragement around open source. These encourage the creation and use of open source, letting them know in no uncertain terms that the strategic leaders at the company are fully behind it. Additionally, if there are certain kinds of licenses we don’t want engineers using, or other open source guidelines for them, our internal documents need to be explicit.”* – Ian Varley, Software Architect at Salesforce.

At a minimum, the document should:

- Explain your company’s approach to open source and the purpose behind the document. What does success look like for your company and what’s the role of open source in achieving that?

“In Autodesk’s case, the reason behind our new open source approach was to make a move to cloud technologies because of how we’re shifting our product focus to integrate even more closely in a cloud environment. The realization follows that if you go to cloud, basically all of that’s built on open source, so you’ve got to ramp up your open source strategy.”* - Guy Martin, director of Open at Autodesk (Open@ADSK).

- Specify how you want developers to consume open source code:

- What if code comes into one of your products from a project with a different licensing setup?

- What acceptance, rejection, and exception policies should developers follow?

- What is your organization’s overall stance toward open source development?

- A good strategy document provides explicit answers to these kinds of questions.

- Specify how you want developers to contribute code to open source projects, and identify projects that are critical to your business strategy. (And encourage them to contribute!)

- What if a developer wants to contribute code from one open source project to the one you are working on but the two projects have different licenses?

- How can your contributions to open source serve a virtuous cycle, so that your projects benefit from contributions in turn? These considerations are part of defining strategic contributions.

“If you are relying on an open source project heavily for your product and you don’t have a seat at the table in terms of leadership and strategy for that project, your business is at risk.” - Guy Martin, Autodesk.

- Provide guidelines for making new decisions, and encourage program buy-in and commitment:

- Should business governance of open source be separated from technical governance?

- How can you make employees champions for open source?

- A good strategy document provides answers and should also clarify your organization’s overall stance toward developing with and around open source.

- Align your business objectives and management directives:

- Which types of open source projects directly align with your business goals?

- Lay out a usage policy and trademark that fits your code and concepts:

- Branding an open source project properly is as important as branding any invention, and there should be no questions about usage policies.

- Provide specifics on open source best practices:

- Successful open source projects have rich developer communities and are often productized in commercial products that profit businesses.

- Which specific practices can best foster this kind of sustainable ecosystem?

- Answer questions as they evolve over time. A good open source policy document should include a FAQ, and answers to common questions should be provided continuously in the FAQ over time.

“FAQs are highly tuned to the questions users and developers actually ask — as opposed to the questions you might have expected them to ask, and therefore, a well-maintained FAQ tends to give those who consult it exactly what they’re looking for. Good FAQs are not written, they are grown. They are by definition reactive documents, evolving over time in response to the questions people ask.” *– Karl Fogel, Producing Open Source Software.

How to create an open source strategy

The first step in crafting an open source strategy is to decide who should be involved in setting the strategy. This means not only deciding which internal business partners should be involved but deciding whether external strategic help and resources should be sought.

External resources

There are many external resources that can help you flesh out your open source strategy, and the good news is that many of them are free. The Linux Foundation offers extensive educational resources that can help you usher in the right strategy, and books like Best Practices for Commercial Use of Open Source Software can provide guidance.

The Open Source Guide produced by GitHub also contains many resources on helping you build or contribute to an open source community.

Google open sourced its open source policy documentation and it can serve as a create template to create your own internal policies.

InnerSource Commons, specializes in helping companies pursue open source principles and practices as well as exchange ideas for internal, proprietary software and infrastructure development.

Another excellent resource for open source strategy is a blog called Changelog. It includes a podcast that covers a lot of different open source topics, called “Request for Commits.” The podcast tackles everything from the human side of creating open source software to questions about business models and strategy.

Note that many companies inside and outside the technology industry have very sophisticated open source programs. You can, and should, learn from them. The way they approach open source differs according to their own needs, but you can choose and adapt the practices and strategies that fit your business best. The TODO Group at The Linux Foundation was created to bring these companies together to share and evolve best practices. TODO also offers a set of free open source policies and templates on GitHub that you can use and contribute to.

General Electric might not be the first company that you think of when it comes to moving the open source needle, but GE is a powerful player in open source. GE Software has an “Industrial Dojo” – run in collaboration with the Cloud Foundry Foundation – to strengthen its efforts to solve the world’s biggest industrial challenges. GE derives benefits from the partners it works with in these efforts, and vice versa.

Among other organizations that have rolled out professional, in-house programs focused on advancing open source and commercializing tools, Netflix is a true standout. It is well worth visiting visit the company’s Open Source Software Center. Netflix has contributed many useful tools and applications to the open source community, ranging from machine learning and orchestration applications to utilities that run on its platform, many of which have been tested and hardened at scale. Netflix, in turn, gets contributions that help its platform run more efficiently, and its open source endeavors have opened doors to various partnerships.

Internal resources

While these types of external resources can provide critical guidance and serve as a benchmark for your own strategy, internal collaboration is key in setting your open source business strategy. Your open source strategy should be tailored to your own unique business model, and the people within your own company are the best source of information. Additionally, you need to include all the stakeholders to reach consensus to ensure that everyone is on the same page and invested in seeing the efforts succeed. For example, it is important to involve executive leadership in the collaborative process.

Creation of an open source program can be invaluable at this point. The TODO Group’s open source guide titled Creating an Open Source Program states: “By creating an open source program office, businesses can enable, streamline and organize the use of open source in ways that tie it directly to a company’s long-term business plans. An open source program office is designed to be the center of the universe for a company’s open source operations and structure, helping to bring all the needed components together.”

An open source program office can help determine policies for code use, distribution, selection, auditing, and more. It can also provide guidance for training developers, ensuring legal compliance, and building community engagement. According to the guide, “The office can also provide advocacy and communications about all things open source inside and outside the company.”

“The only way you get hearts and minds (to advance your open source strategy) is to find the people in the individual teams that are willing to be proactive.” - Guy Martin, director of Open at Autodesk (Open@ADSK).

When choosing internal staffers to help set strategy, remember that it is critical to involve people who are qualified to supply business and legal governance of projects as well as people who can supply technical governance. For example, an employee with technical skills may have an understanding of current open source practices and might be qualified to set policies such as Inbound Contribution Guidelines, while a person with business credentials might be more qualified to set policies regarding trademarks. Conversely, an employee with legal qualifications is best for defining licensing policies. And, of course, it is essential to identify stakeholders who have true passion for open source. Considerations for open source program office structure and discussion of the various management roles are detailed in the open source guide mentioned previously.

How can you engage all of your stakeholders? Start by talking and, crucially, listening to what’s working and what isn’t. The way you engage will depend on what works for your company and its existing culture. But it always pays to do the research before you dive into the strategy.

When Guy Martin first started as the open source director at Autodesk, he asked his boss for two lists: “I said, I’d like a list of people who believe in what you’re trying to do with (open source) and why you hired me in this initiative. And I want a list of people who either flat-out don’t believe it’s going to work or who may be on the fence.” Then Martin talked to everyone on those two lists. The detractors helped identify where the stumbling blocks were going to be for their business. And the champions were the people he approached to help him build the program.

Key considerations

We’ve touched on the critical components of your strategy document and how to go about creating it. Now, here are two really important considerations in creating your strategy: governance and sustainability.

These concepts will set the philosophical framework for your program, determine how it runs, and ultimately help determine how/whether you can maximize your open source strategy.

Consideration 1: Governance

Before you set an open source strategy, you’ll likely have many disparate processes in place – across teams and departments, product teams and IT, etc. – to consume code or contribute upstream. Getting standardized governance in place is key to streamlining and optimizing processes, which makes it easier for developers to participate. It also helps get everyone on the same page and provides the foundation for measuring progress toward your goals and reducing risk. If everyone is following the same policies and processes, it’s much easier to pinpoint and address any roadblocks that may be happening.

“I didn’t want a 10-week process with 500 pages of documentation for a 5-line bug fix, so I worked with legal to create a streamlined workflow that an engineer could accomplish in a reasonable amount of time.” - Guy Martin, director of Open at Autodesk (Open@ADSK).

Your strategy should be very specific about open source governance within your organization and outside it. Proper governance requires specific policies and processes, but should also guide the culture that surrounds the building, deployment, and maintenance of open source software. In particular, open source culture is geared toward transparency, openness, and encouraging participation from diverse contributors.

“There are open source projects where external contributions are welcome, but the road maps and the governance of the projects are very much in the hands of a single company. Then there is truly community-driven open source. Which kind of projects are you working with?” - Joe Beda, co-founder of Kubernetes at Google and co-founder and CTO at Heptio.

Governance can help minimize risks. For example, many developers are comfortable acquiring open source tools online and integrating them with existing code, platforms and applications. However, allowing them to do so without any formal acquisition process in place means courting significant risks ranging from security risks to legal risks. Likewise, open source licenses and policies can have a huge impact on an organization’s control over technology and intellectual property portfolios. In addition, for open source projects that also have commercial editions, it is worth considering whether external stakeholders should be involved in governance.

Having an internal governance structure which closely maps external open source community structures also streamline the “context switch” of your developers when working on projects directed towards internal efforts as compared to external contributions. It also eases the transition when an internal project is eventually open sourced, since the developers are already working in that governance mode.

“One of the things that we’ve tried to engender in the Kubernetes community is the idea of project over people or company. What’s good for the project is a separate question from what’s good for the companies that are involved with the project. When you end up with open source projects that are too tightly tied to a single company, really sticky issues can arise.” – Joe Beda, Heptio.

Consideration 2: Sustainability

A key driver to succeeding with your open source program is building a strategy around encouraging other companies to take dependencies on your open source projects. Long-term, sustainable projects arise from feature-rich developer communities whose code is productized in commercial products that profit businesses which in turn reinvest back into the projects. The goal is to enable a virtuous projects build products that generate profits that get reinvested back into the project community lifecycle.

Partnerships, contributor agreements and commercial dependencies can drive a virtuous cycle of commercial and community engagement based on accepted governance and IP models. An intelligently defined open source program can help drive all of these. What is your organization’s policy toward sharing and monetizing open source inventions and driving partnerships and commercial dependencies?

For example, many open source tools are offered in free editions online but also exist in fee-based, supported instances, and it is common for outside contributors to advance platforms and applications that are offered commercially. It is wise to define in your strategy document exactly how such editions differ and how control is exerted over them, keeping in mind that levels of control can vary widely over time.

Other components

Beyond the critical elements of your strategy discussed earlier, there are many other policies to lay out in your strategy document. The good news is that there are free guidelines from trusted external sources that you can take advantage of.

For example, Synopsys offers a useful four-pillar set of guidelines for setting your open source strategy:

- Define strategy for building open source platforms and applications

- Define strategy for building with open source, such as integrating existing products and services with open source tools

- Define strategy for building for open source community, such as encouraging contributions to and involvement with existing projects

- Define strategy for building on open source, including internal replatforming or application rollouts based on open source

In addition to these strategic pillars and guidelines on governance, here are some other key components to include in your strategy document:

- Goals. Define your goals for your business strategy and how open source can drive achievement of your goals. For example, many companies are currently transforming their platform infrastructure by moving to open cloud platforms such as OpenStack. In many cases, this is because they studied the ROI they could get by moving infrastructure to the cloud, determined what levels of vendor lock-in they could avoid, and set goals for specific financial milestones they want to achieve.

Build a holistic set of goals for your strategy document, with metrics for achievement. Among metrics to track, consider reporting on increases in upstream contributions, cuts to development costs, and increases in recruitment of maintainers. In addition to these metrics, your inventory of business objectives and goals should provide specifics on open source leadership milestones, and project security and performance advancements. Also, though, keep in mind that there are no magic metrics.

“Find metrics for each community that you’re working with. I tend to find metrics based on what a specific community is feeling as pain, and try to change those metrics for the better. There is no one, magic assessment where if you look at six metrics, ranging from pull requests to contributor numbers, you can suddenly pronounce your community and ecosystem healthy. " – Sarah Novotny, Kubernetes community program manager at Google.

Management Plan Once your strategy document includes specific goals, ensure that it also sets out specific actions to achieve your open source business objectives, and assign roles and responsibilities for tracking progress. The most important part is to get buy in for your executive management chain.

Provide specific KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) for tracking the achievement of goals.

Policies and processes. In addition to licensing and rules for accepting contributions and outside code, managing policies and processes is key. The TODO (Talk Openly Develop Openly) Group at The Linux Foundation offers free open source policy examples and templates on GitHub.

Partnerships and acquisitions. Partnerships and acquisitions are key parts of a successful open source business strategy. Your strategy document should be specific about goals in these areas, and should lay out key strategic partnerships that your organization may have with other organizations such as TODO, The Cloud Foundry Foundation, and more.

Patents and IP. Patent rights and intellectual property guidelines can have an enormous impact on how inventions are used, and in many cases commercially leveraged. Your strategy document should be specific about your patents, rules pertaining to patents, and your IP guidelines. If your organization has a separate IP strategy, ensure that your open source strategy is aligned with it.

Foundations and sponsorships. Open source foundations and other nonprofit organizations have had an enormous impact on the world of open source in recent years. Your organization can benefit from working with foundations ranging from The Linux Foundation to the Eclipse Foundation to the Apache Software Foundation, and you may even benefit from launching an open source-focused foundation. Your strategy document should supply any existing partnerships and plans for working with foundations.

“Foundations provide a lot of value. Without them, it has historically been hard for a lot of very critical projects to get the funding they need to be well maintained. They help ensure a level playing field and they provide mechanisms for organizations to give back to open source projects without contributing developers directly.” — Luke Faraone, software engineer at Dropbox.

- Inbound Contribution Guidelines/Metrics. Your strategy can derive enormous benefits from inbound contributions (see our section on considerations for sustainability.) Your strategy document should provide both guidelines and metrics for contributions.

You don’t have to build your policies in this area from the ground up; the Contributor Covenant is a rock solid code of conduct and contributor guidelines document that is used by over 40,000 open source projects, including Kubernetes, Rails, and Swift. Likewise, organizations such as The TODO Group, The Linux Foundation, and Synopsys have extensive experience with setting inbound contribution guidelines.

A good inbound contribution strategy also includes carefully documenting your APIs — always a best practice. OpenAPI has emerged as the industry standard for describing RESTful APIs.

“One of the most important things when building an open source community is making sure that your own processes are open. The more transparent you can make your decision-making processes, the more of a sense of ownership your community will have. You also want to make sure that your process doesn’t become a blocker. If your open source process for either inbound or outbound contributions is onerous, people will look to bypass the process or simply decide that contributing is too difficult.” – Luke Faraone, software engineer, Dropbox

“You need to give people ways to get involved with your projects that don’t require them to have a PhD or to have been working in a similar area for 25 years. You need ways for them to get involved quickly. That means that you need really good setup documentation, and it also means having active and healthy forums.”- Ian Varley, software architect at Salesforce.

When and how much to invest: determining ROI

There is no way to wave a magic wand and find the exact benefit you will get from your open source program, but there are guidelines for how to approach it. You must consider how return of investment (ROI) relates to your strategy. The bottom line is that the return on investment that you can derive from your open source strategy should be considered from numerous angles.

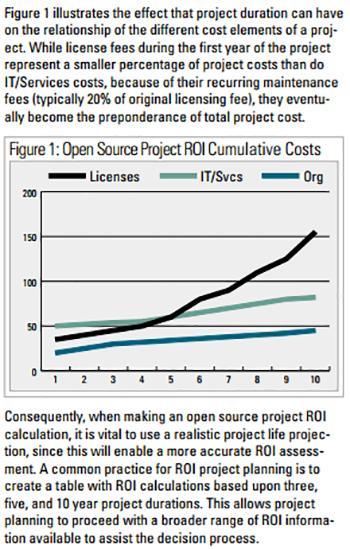

First, you must weigh the benefits of open source with the risks and costs of managing it. A free, joint white paper (PDF) from Novica and OpenLogic provides many specific ways to calculate open source ROI and strategize around it. For example, the following graphic from the white paper shows that the duration of project development has a profound impact on various elements of ROI calculation, ranging from licensing expenses to IT/Services expenses:

As you go about calculating ROI, keep the following guidelines in mind:

- Calculate the benefits in cost savings. Of course, a key metric to evaluate in determining the benefits of your open source strategy is calculating cost reduction. Evaluate both cost savings from open source deployments and open source inventions, taking into account savings on licensing fees, hardware, support, and more.

Support is a major cost center for many organizations, and if you can reduce costs for support, you can reap big financial benefits. Likewise, what specific hardware and licensing costs might you eliminate by, say, moving to open source platforms ranging from Linux to OpenStack? In the case of open cloud platforms, for example, storage and compute resources in the cloud can entirely eliminate the need for many such resources in-house. Also keep in mind that although “free” open source software may not have the same licensing fees as proprietary software, it comes with a development cost involved in contributing upstream, integrating it with other offerings, and more.

Calculate the benefits by reach and conversion. By tracking the reach of open source projects you create, you can gather useful information, and in some cases gauge conversion for your organization’s products and services. Package managers such as npm and RubyGems.org can be used to distribute open source projects, subsequently allowing you to track downloads. Many organizations put their projects on GitHub, where the “Traffic” page can detail how many times a project has been cloned and much more. These metrics can aid brand awareness around your projects, likeliness to gain contributors, and more.

Do an operational risk assessment. The Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP) recently added “using components with known vulnerabilities” to its top 10 list of risks, and open source software can introduce vulnerabilities in some cases. An open source software security audit gives you visibility into the components and the vulnerabilities within your code. Black Duck performs these, and tools such as Wireshark and Nikto can identify vulnerabilities and problems.

Avoid legal risk. Operational risk and legal risk are different, but assessing both is important. Legal risks around open source can include costs from legal actions surrounding using the wrong license, costs from merging code between projects that have disparate licences, and more.

The Open Source Definition is where you should start to understand how open source projects should be licensed, and what actually qualifies as open source. It’s also good to review Open Standards requirements.

You must also assess what kinds of licenses your projects should have. The Software Freedom Law Center (SFLC) offersa set of online resources on how open source licenses and copyrights work, and much more. And, a simplified matrix of license features can be found at Choosealicense.com.

You’ll also want to consider the costs and benefits of license compliance. The cost of not complying with an open source license may be steep and involve lawsuits. The Linux Foundation’s Open Compliance program offers several resources including publications, training materials, and a free training course for developers. (You can also see our guide on Using Open Source Code which outlines a baseline compliance program.)

Legal issues should, of course, be assessed by your own legal personnel. The SFLC authors are attorneys who were part of creating popular open source licenses. It’s also an excellent idea to keep up with current and archived editions of the International Free and Open Source Software Law Review.

Deciding where to invest

Investing in open source can be approached from numerous angles, including leveraging in-house resources and external ones. Keep in mind that devoting developer resources to open source and upstream contributions are part of investing in open source. It is important to understand how incoming and outgoing code and projects are arriving and being distributed.

Identify which open source projects are critical to delivering products or services. Once a company understands its IP portfolio and the open source contributions its developers want to make, it can work to ensure its developers are empowered to make those contributions.

Conduct an internal audit. Have you acquired open source tools and platforms through acquisitions and are you getting the maximum benefits from them? Assess this in your audit.

Identify which internal projects you could open source.

You can also structure good ways to identify open source projects that either exist in-house at your organization or should exist. For example, many Silicon Valley companies have internal competitions and hackathon events that offer employees top prizes for their best open source inventions. Through these, companies ranging from PayPal to Google have employee-invented open source creations built into their own fabric and product portfolios.

“One great thing that happens during a hackathon is the power of recombination – of inventors saying ‘I know one way to do this, and over here is another project that aids that process, and I can put these things together.’ If everything is closed source, the problem is that you have a lot fewer building blocks to work with. By contrast, the world is your oyster with open source. You have so many more building blocks available to you.” – Ian Varley, software architect at Salesforce.

Next, turn to external resources to help pinpoint projects that you’re not yet using or participating in, but that may have a business benefit. There is tremendous leverage in choosing the right open source projects and communities at the outset. Selecting strategically important projects for focus is critical.

Partner with other organizations. They can help you choose the best projects to get involved with and identify what projects they are reaping benefits from. And there are several independent organizations that can help. The Linux Foundation, TODO Group, Innersource Commons and Open Source Initiative can all provide guidance.

Examine which projects other organizations in your industry contribute to. They can steer you toward the right projects to get involved with. For example, many telecoms are reaping big benefits from open Network Functions Virtualization (NFV) technology that can eliminate historically proprietary components in telecom technology stacks. Some of these companies work with The Linux Foundation on NFV initiatives and there are several working groups that focus on NFV. These industry-focused working groups can provide you with valuable guidance.

Are you interested in more resources to help you set your strategy? Here are some excellent ones:

Measuring Open Source ROI

Open Source Return on Investment

Launching Successful Open Source Projects

The Linux Foundation on Starting Successful Projects

Legal Resources

Licensing

Contributor Code of Conduct

Open Source Policy

Open Source Strategy Blog

Open Source Strategy Podcast

Acknowledgements

Contributors:

- Andrew Aitken, Global Open Source Practice Leader, Wipro

- Chris Aniszczyk, CTO, CNCF

- Joe Beda, co-founder of Kubernetes at Google and co-founder and CTO at Heptio

- Luke Faraone, software engineer at Dropbox

- Jim Jagielski, Open Source Chief at Consensys

- Guy Martin, director of Open at Autodesk (Open@ADSK)

- Sarah Novotny, Kubernetes community program manager at Google

- Ian Varley, software architect at Salesforce